I'm in London, doing research, which is fantastic--but it means that I feel guilty blogging when I should be writing something more weighty and academic.

So, until I get a free moment, enjoy the following links--with commentary:

The "Slow Reading" Movement

There's been an explosion of "anti-web-reading" articles/books recently, but the (at least attempted) movement here is interesting because it tries to link basic textual analysis ("close reading") with the sensual enjoyment of food advocated by the "slow food" movement. I like it--it addresses a serious problem I've seen in my own classes of students trying to skim texts that can't be skimmed--but I don't think any of this stuff will work unless we beef up requirements for the number of arts and literature courses at colleges and universities everywhere. (And therefore, the number of teaching jobs available…)

Digested Read

Now I contradict myself with a link that provides digests of recent books. But really, these two links cohere into a unified theme: the only thing worse than our collective inability to understand written material is our desperate urge to produce written material. Only a tiny percentage of us (here I should just blow my cover and say, "them") manage to do this and get it published, but that's still a lot of new vampire books and celebrity tell-alls per year. If you're reading the right (slow) way, you can't keep up with the flood. Luckily there's John Crace, who writes beautifully cruel, 700-word digests of recent publications. Are they fair? I don't know, because I haven't read the books…and what I love about Crace is that he convinces me that I was right not to.

"Top 100 Books of All Time"

This is old news, I guess, but I saw it under the Guardian's "Most Viewed" while browsing "Digested Read". (It's still in "Most Viewed," 8 years on!) Sadly, it appears that the people who compiled the list accidentally swapped it with another list they were compiling at the same time: "Books Literary Types Should Recommend to Others, As If They Had Read and Enjoyed Them".

Links: London Literary Edition

Book: Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (1847)

Since I haven't read the Twilight series, and I don't consider myself particularly sappy, I was surprised to find myself siding with (randomly selected) Twilight fan Hayley Mears, whom the Guardian quotes in an online review saying: "I was really disappointed when reading this book, it's made to believe [sic] to be one of the greatest love stories ever told and I found only five pages out of the whole book about there [sic] love and the rest filled with bitterness and pain and other peoples [sic] stories".

"Bitterness and pain" is right. (And all the [sic]s in there are right, too, because this book is pretty [sic].) Essentially, this is the story of two snarling, brutish, semi-wild children who love each other in their animalistic way, but don't get together because one of them, Cathy, thinks she needs to marry someone with class and money. Her dismissal of Heathcliff, the vicious foundling she loves, for Edgar, the wimp who loves her, sets off a chain of about three-hundred pages of slow, conniving cruelty, as Heathcliff labors to destroy everyone involved in the affair, as well as their children, houses, and distant relations.

Academically, there are a few interesting things going on here. Wuthering Heights can be read as an early Victorian response to (or reworking of) Romanticism, and its approaches to nature and love are surprising for the way they show sympathy for a form of rawness that's otherwise unappealing (and uncharacteristic of the period). As a devotee of both the Burkean sublime and Nietzsche, I was interested in the interplay of rough, calamitous nature, the animal, and Heathcliff's slow-burning vengefulness…which all fits partially, but not very neatly (that's the interesting part), under those two moral/aesthetic frameworks.

But while a book's being "interesting" is normally enough to get me to like it, it wasn't enough here. At one point in the novel, Heathcliff expresses a wish to vivisect the other characters, and vivisection is a good metaphor for the novel as a whole. Reading about Heathcliff is like watching a troubled teen slowly cut a wriggling fish apart--you get upset at the cruelty of the thing, but the whole affair doesn't have much dramatic interest; you walk away feeling bored, sad, and wondering what the point of it all was. The novel doesn't have the psychological insight of a Jane Eyre, or the social complexity of a Bleak House. Curious readers, I give this one an "avoid."

Books That Matter: Ishmael

The controversy surrounding Ishmael began even before its publication--it won the massive, one-time-only Turner Tomorrow Prize, and immediately the highly literary judges who chose it began to denounce the selection process. (They said it required them to give too much money to one book in a pool of titles they weren't over-the-top enthusiastic about.)

The controversy surrounding Ishmael began even before its publication--it won the massive, one-time-only Turner Tomorrow Prize, and immediately the highly literary judges who chose it began to denounce the selection process. (They said it required them to give too much money to one book in a pool of titles they weren't over-the-top enthusiastic about.)

Personally, I remember my mom reading Ishmael as part of a book club when I was a little kid, but I didn't read it myself until college, when it was the chosen selection of a backpacking group I was involved in. I'm hesitant to include it on any list of "books that influenced me" because of its cultish appeal...it's one of those books, like Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, or any Ayn Rand novel, that seems to pigeonhole you as a certain type the second you admit that it mattered to you.

Still, it did matter to me, because it was the first thing I read that really drove home the ethical implications of the idea that evolution is not directional. It wasn't until I read Ishmael, in other words, that I recognized that every time someone uses a phrase like "saves lives," they only mean "human lives"--and that, world as it is, saving human lives implies significant destruction of other forms of life, often at a permanent, species level that alters and destroys ecosystems.

This is where the "we can have it all" do-gooders jump in and say "We can save both! We can save human lives, and help the world, and if you save humans then, in the long run, environmental impacts decrease!" But that kind of optimism seems like an excuse not to confront the problem, so that while we wait for the (uncertain) effects of the environmental Kuznets curve to kick in, the world--the real world, not just the human world--disintegrates.

It made me realize that every "charitable" decision made to help another human being already contains a dangerously unexplored ethical decision, because it narrows charity to the species that needs it the least. Whatever you want to do in the face of that realization, I think it's important that people realize it. Unfortunately, most of today's philanthropists (a word that literally means, in Greek, "human lovers") cheerfully sweep it under the table.*

So I thank Ishmael for turning me into the kind of smart aleck who listens to your heartwarming description of some wonderful humanitarian, then raises a finger and says something like, "Excuse me, but it seems you're being anthropocentric. You only care about your own species, so even your idea of charity is secretly selfish." Then I smirk and walk away, because I'm even more self-righteously selfless than you are.

*See, for instance, this recent article by Peter Singer, who wonders whether people should stop reproducing...but only because he's worried about human suffering from climate change. (Any emphasis on suffering is a sign that the speaker is primarily worried about humans and human-like creatures, who suffer in ways recognizable to humans. Additionally, it seems like a minor tragedy that worrying about "climate change" has become almost synonymous with "environmentalism.") Or check out this profile of Melinda Gates and the Gates Foundation, where Bill Gates expresses concern about human overpopulation...only to forget about it at the first mention of a possible (and, I think, majorly inadequate) counterargument. Needless to say, both the Gates Foundation and Singer are considered revolutionary thinkers in the world of philanthropy--the Vogue profile notes that the Gates Foundation focuses on "problems that nobody else seems to care about"--and even they can't seem to get past a humans-only orientation. Sigh.

Six High Culture Degrees of Kevin Bacon

A friend sent along this chart from Lapham's Quarterly. New rule: any diagram that can connect Kevin Bacon, Queen Victoria, and James Agee will be posted to Nifty Rictus without delay.

A friend sent along this chart from Lapham's Quarterly. New rule: any diagram that can connect Kevin Bacon, Queen Victoria, and James Agee will be posted to Nifty Rictus without delay.

Vocablog: tumulous

tumulous, adj.

Heaped up; mound-like.

(Found in Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure.)

Usage example: She waited so long to clean her dishes that tumulous towers of teacups spread across the kitchen.

Easy Rider, Not-So-Easy Politics

"Idea of the Day" over at the NYT is drawing attention to the debate around the politics of Easy Rider, as briefly summarized in an obit of Dennis Hopper written by the libertarian magazine Reason.

Like most debates about the "political message" of any cultural object, this one intrigues at first, but quickly becomes boring. The main reason is that any cultural artifact that really succeeds among sophisticated critics over the long-term tends to be rich, complex, and unpredictable: almost by definition, it does not have a single message, political or otherwise...its message changes with its contexts.

A ludicrous metaphor should help explain how silly this form of interpretation is. Trying to determine whether a work of art generally supports left-wing or right-wing causes is like trying to determine whether a kitten generally faces East or West. First, you're using a simplistic measure ("left or right? East or West?") in a reality that has a lot of other possible orientations. Then, you're applying that bad framework to a highly unstable object that, in its ideal state, will change directions frequently, or challenge the notion of directionality in the first place.

The only interesting thing about these kinds of readings is watching how the interpreter turns somersaults to try to claim that his inadequate tools fit the complexity of real life, or real art--and there can, occasionally, be a kind of artistry even in those gymnastics. But for the most part (especially on the internet), the exercise of showing how a work is "progressive," "conservative," or "apparently-conservative/progressive-but-secretly-progressive/conservative" can only go so many ways, and those ways are all well-traveled. It's time to prioritize new, more interesting approaches.

Bing Has Great Ads, the iPhone...And Nifty Rictus

Bing, Microsoft's johnny-come-lately of search engines, just earned major points in my book. Their ads are catchy--and omnipresent--but I never understood how they could possibly compete in a market dominated, even saturated, by Google and Yahoo!.

Until tonight, that is. It was recently announced that the new iPhone will carry Bing, in addition to Google, as a search option. I guess that's good news for them, but what really caught my attention was not what's carrying Bing, but what Bing is carrying. That's right: Bing is now indexing Nifty Rictus.

For those even less knowledgeable about these things than I am, that means that a search for "nifty rictus" on Bing turns up this blog, while a search on Google or Yahoo! turns up "0 results" or results limited to pages (like my web site, or my old blog) that link to this one. One of the fastest ways to appear in the search results on a search engine, of course, is to submit your site for indexing. Given my skepticism about Bing, I submitted "http://niftyrictus.blogspot.com" to Google a few weeks ago, then to Yahoo! about a week ago, and finally to Bing a day or two after that. Not only was submitting to Bing far easier than submitting to, say, Yahoo! (which forces you to open an account with them to submit a site), but its turnaround was the fastest--which surprised me, since this blog is hosted by a Google subsidiary.

So thanks, Bing...and I apologize about my lack of faith in you. I was already using your ads as reference points to help explain why certain people are bad conversationalists and bad classroom participants. (I swear I had a class with a version of the search overload guy in it--see below.) Now I see that your strength isn't just advertising. I think you've made the right decision, boosting my little blog when all the big search engines just smirked. I'll try not to let you down.

Facebook and Photographic Nostalgia

Wow--I definitely hadn't seen this before. Among Facebook's eerie new suggestions: that you go back through your old uploaded photographs and reminisce. (They call it "Photo Memories"...meaning, I guess, memories of photographs that themselves record memories?)

That's always been a function of the display album, of course. Sitting on your living room table or bookshelf, an album seems to demand occasional perusal. Now that your photographs are stored remotely, and albums have migrated from the parlor to the social portal (something I wrote about in Afterimage a couple of years ago), it would seem to be less of a possibility. Cue Facebook, which has programmed in the old suggestiveness of the album on the table--presumably to increase its own "stickiness" for commercial reasons.

While it's become trendy to vilify Facebook at the moment, this commercial cultivation of nostalgia is an old trick, especially in photographic circles, and it was always one of the selling points of photo albums. For someone who loves the whole idea of the photograph album, it's interesting to see its old functions conserved or repurposed in this new format.

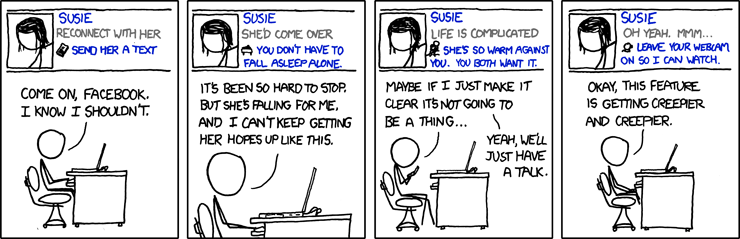

(I can't resist including xkcd's take on Facebook's prodding suggestions...)

Vocablog: flagitious

flagitious, adj.

Wicked; drawn to evil or criminal behavior.

(Found in Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Aurora Leigh.)

Usage example: You didn't accidentally lose my iPod--you stole it, you flagitious dog.